From the fleeting flutter of a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis to the stoic germination of a sixty-year-old redwood seedling, every organism is a testament to life's most fundamental mission: continuity. The intricate dance of Reproduction, Life Cycle & Offspring Care isn't merely about creating new individuals; it's a profound, adaptive saga that unveils diverse survival strategies honed over billions of years. It’s the story of how DNA, the universe’s most exquisite self-replicator, orchestrates an unbroken chain of existence, ensuring that life, in all its astonishing forms, persists, evolves, and thrives against all odds.

This isn't just biology; it's the very heartbeat of existence, a meticulously choreographed symphony of growth, change, and renewal that underpins every species on Earth.

At a Glance: The Enduring Dance of Life

- Life is a Full Cycle: Reproduction encompasses an organism's entire journey, from its nascent form (like a fertilized egg or spore) through growth, maturity, and the capacity to create the next generation. It's not just about the "adult" stage.

- DNA's Central Role: At its core, life's continuity relies on DNA's unique ability to self-replicate, guiding the precise and orderly changes that occur across generations, supported by specialized enzymes.

- Vast Diversity in Time & Form: Life cycles vary dramatically in length and complexity, from bacteria completing their cycle in minutes to giant sequoias taking decades to mature. Larger organisms generally exhibit greater complexity and require more elaborate systems replicated over generations.

- Plant Metagenesis: Plants, along with many algae, showcase "alternation of generations" (metagenesis), cycling between distinct haploid (gametophyte) and diploid (sporophyte) multicellular stages.

- Animal Metamorphosis: Many invertebrates undergo metamorphosis, a radical physical transformation where an organism essentially builds a new life history on the foundations of a previous larval stage.

- Natural Selection's Hand: Charles Darwin's principle of natural selection is the fundamental explanation for how reproduction evolves, favoring strategies that optimize survival and perpetuate successful variations.

- Controlled Variation is Key: While reproduction ensures copies, variation is crucial for adaptation. Sexual reproduction is a primary mechanism for generating and controlling this necessary diversity, enabling rapid adaptation and trait combination.

- Offspring Care Spectrum: Species employ diverse strategies for offspring care, ranging from producing countless progeny with minimal parental investment to nurturing a select few with intensive, prolonged support.

Beyond the Adult: Understanding the Full Life Cycle

When we talk about an organism's reproduction, it's easy to picture a mature adult producing offspring. But that's only a snapshot. The scientific lens reveals a much broader, more fascinating picture: reproduction encompasses an organism's entire life cycle, from the moment a new genetic blueprint is formed (say, a fertilized egg or a single spore) all the way through its development, growth into an adult, and finally, its own capacity to contribute to the next generation.

Think of it as a continuous loop, a journey rather than a single event.

The DNA Blueprint: Replication's Foundation

At the heart of this intricate process lies DNA. It's the only molecule we know capable of true self-replication, creating a series of copies that undergo exact and orderly changes over time. These changes are precisely guided by the genetic code within the DNA, supported by a tireless team of DNA-derived enzymes that facilitate every step. Without this remarkable molecular engine, the continuity of life as we know it would simply be impossible. It's the ultimate instruction manual, constantly being copied and refined.

From Microbe to Sequoia: A Spectrum of Survival Timelines

The sheer diversity in life cycles is astonishing. Consider the extremes: a humble bacterium might complete its entire life cycle, from division to division, in a mere 30 minutes. In that tiny span, it duplicates its DNA, grows, and splits, ready to begin anew.

Now, shift your gaze to the towering giant sequoia. This majestic tree embarks on a vastly different timeline, taking an incredible 60 years just to produce its first fertile seeds. That's a life cycle approximately 10 million times longer than a bacterium's! This immense difference isn't just about size; it reflects a radical increase in complexity. Larger organisms, like the sequoia, require elaborate systems, specialized organs, and diverse tissue types—all of which must be duplicated and developed across generations, demanding more time and resources.

The Green Kingdom's Grand Designs: Plant Life Cycles

Plants, the silent architects of our world, follow deeply structured life histories. Their journey typically unfolds through distinct, sequential epochs.

The Five Epochs of a Plant's Journey

- Seed Formation: It all begins after fertilization, when numerous cell divisions create a tiny embryo, safely encased within a protective seed coat. This is the ultimate promise of future life, a miniature plant awaiting its moment.

- Dormancy: Many seeds enter a period of inactivity, sometimes prolonged, where they patiently wait for the right conditions—moisture, warmth, light—before awakening. This strategic pause allows them to survive harsh environments.

- Germination: The magic moment when the seed sprouts, pushing a root downwards and a shoot upwards, marking the true beginning of independent growth.

- Adult Emergence: The young plant grows, its shoots lengthen, roots spread, and the stem thickens. Interestingly, the juvenile forms of many plants can look significantly different from their mature, reproductive counterparts.

- Flowering/Gamete-Bearing Period: This is the reproductive stage, where the plant produces flowers, cones, or other structures essential for creating gametes (sperm and egg) and ultimately, new seeds.

Alternating Realities: The Haploid-Diploid Dance (Metagenesis)

A core concept unique to the Archaeplastida group (which includes algae and all land plants) is the alternation of generations, or metagenesis. This isn't just a simple cycle; it's a sophisticated interplay between two distinct multicellular forms, one with a single set of chromosomes (haploid, n) and another with a double set (diploid, 2n).

Here’s how this fascinating dance unfolds:

- Fusion: Haploid gametes (like sperm and egg) from two different parents fuse during fertilization to create a single diploid zygote.

- Sporophyte Development: This zygote then undergoes multiple rounds of mitosis, developing into a multicellular diploid organism called a sporophyte. Think of the large fern you see, or the main body of a flowering plant – that’s the sporophyte.

- Spore Production: The sporophyte, at maturity, produces specialized cells called sporocytes. These cells undergo meiosis (a type of cell division that halves the chromosome number) to form haploid spores.

- Gametophyte Development: These haploid spores then germinate and divide by mitosis to form a multicellular haploid organism known as a gametophyte.

- Gamete Production: The gametophyte matures and produces new haploid gametes, ready to fuse and restart the cycle, completing the loop.

This alternating strategy allows plants incredible flexibility in diverse environments.

Evolution's Masterpiece: The Shrinking Gametophyte

Over evolutionary time, we observe a clear trend in higher algae and vascular plants (like ferns, conifers, and flowering plants): a reduction in the size and prominence of the haploid gametophyte phase (the haplophase) and a corresponding increase in the diploid sporophyte phase (the diplophase).

For instance, in mosses, the fuzzy green cushion you see is primarily the gametophyte, with the sporophyte being a smaller, often short-lived structure dependent on it. In ferns, the large, leafy plant you recognize is the diploid sporophyte, while the haploid gametophyte is a tiny, heart-shaped structure called a prothallus, living independently on the soil surface.

Fast forward to higher plants—conifers and flowering plants—and the gametophyte becomes almost microscopic, entirely enclosed and protected within the tissues of the large, dominant sporophyte (e.g., pollen grains and the embryo sac within the flower's ovary). In most animals, and indeed in higher plants, the haploid tissue is strictly confined to the ovary or testes of the large, diploid organism. Wilhelm Hofmeister, a pioneering botanist in the 19th century, was instrumental in deciphering and advancing our understanding of this profound concept.

The Animal Kingdom's Transformations: Life's Radical Reroutes

If plants have their alternating generations, animals, especially invertebrates, frequently embrace radical physical changes in their journey through life. This phenomenon, known as metamorphosis, often means an organism appears to live "two life histories, one built on the ruins of another."

Metamorphosis: Life's Dramatic Second Act

The most iconic example is the butterfly. Its life cycle progresses through distinct and dramatically different stages:

- Larva (Caterpillar): A dedicated eating machine, designed for growth.

- Dormant Pupa (Chrysalis): A seemingly inactive stage, but one where profound internal changes occur.

- Adult (Imago): The winged, reproductive stage, focused on dispersal and mating.

The transformation inside the pupa is nothing short of miraculous. Most of the caterpillar's tissues literally disintegrate, providing energy and building blocks for the development of entirely new adult structures, which arise from specialized groups of cells called imaginal disks. It’s a complete biological renovation.

Sea urchins offer another striking example. They start as a delicate, free-swimming pluteus larva. While this larva is still swimming and feeding, an adult bud begins to develop internally. Eventually, the larval tissues disintegrate, providing nutrients and energy for the rapid growth of the adult sea urchin.

These examples highlight that the major differences between organisms aren't always in their adult appearance, but often in their entire, elaborate life history.

Polyps and Medusae: The Dual Lives of Coelenterates

Coelenterates, such as the fascinating Obelia, demonstrate yet another form of life cycle diversity. These organisms often exhibit two distinct phases:

- Sessile Polyps: These are typically colonial hydroids, anchored to a surface, with specialized reproductive polyps that bud off new individuals.

- Motile Medusae: These are free-swimming jellyfish, responsible for sexual reproduction, producing eggs and sperm.

Some coelenterate species may have lost one of these stages over evolutionary time, emphasizing how adaptable and plastic life cycles can be. For example, some jellyfish lineages have abandoned the polyp stage altogether, while some hydroids never produce a free-swimming medusa.

The Engine of Evolution: Natural Selection and Reproductive Strategies

The fundamental explanation for biological reproduction, in all its varied forms, traces back to the powerful force identified by Charles Darwin: natural selection. Without reproduction, there's no evolution.

Darwin's Insight: Reproduction as the Basis of Change

For evolution to occur, a few core conditions must be met:

- Reproduction: Organisms must be able to create copies of themselves.

- Variation: These copies cannot be perfectly identical; they must exhibit some degree of variation.

- Inheritance: These variations must be heritable, meaning they can be passed down from parent to offspring.

- Differential Success: Individuals with advantageous variations are more likely to survive and, critically, to reproduce, thus contributing more offspring to the next generation. This process gradually shifts the traits of a population over time.

The "Principle of Compromise": Striking the Right Balance of Variation

Variation is a double-edged sword. If there's too little variation, a species might struggle to adapt to changing environments, eventually facing extinction. If there's too much variation, beneficial traits might get "scrambled" or diluted across generations, preventing effective adaptation. Natural selection, therefore, constantly seeks an "optimal amount of variation"—a dynamic balance that allows for both stability and necessary change.

Sexual Reproduction: The Ultimate Genetic Mixer

In most plants and animals, sexual reproduction has emerged as the most successful and widespread mechanism for controlling this vital variation. It's ideally adapted to:

- Produce appropriate variation: By combining genetic material from two parents, sexual reproduction shuffles genes in novel ways.

- Incorporate new trait combinations rapidly: This genetic recombination allows beneficial traits that might have arisen independently in different lineages to be brought together in a single offspring, speeding up the evolutionary process.

The evolution of reproduction itself has been a grand trajectory, moving from simple unicellular life forms to the immense complexity of multicellular organisms. This shift necessitated the evolution of "life-cycle reproduction"—a coordinated sequence of growth and development that ensures the creation of new, complex individuals. Species also evolve efficient reproductive strategies, constantly navigating a critical trade-off: Should they produce a vast number of offspring with low individual survival rates, or a few, highly cared-for offspring with much better chances? Natural selection ensures that species consistently produce enough offspring to persist, adapt, and avoid overpopulating their niche, maintaining ecological balance.

Speaking of animals and their life stages, have you ever stopped to think about the unique life cycles of some of the world's most enduring creatures? It's fascinating how different species adapt their reproductive journeys to their specific environments, much like understanding All about marmots reveals their specialized survival tactics in harsh alpine environments.

Mastering Genetic Diversity: How Life Manages Variation

Inherited variation isn't random; it's meticulously managed by the genes residing within an organism's chromosomes. Sexual reproduction, by its very nature, demands a critical single-cell stage—the fusion of haploid gametes (sperm and egg) to form a diploid zygote—where the genetic material of two parents is combined.

A Delicate Balance: Factors Governing Genetic Traits

The amount of variation generated in a population is precisely controlled by an interdependent and balanced set of factors:

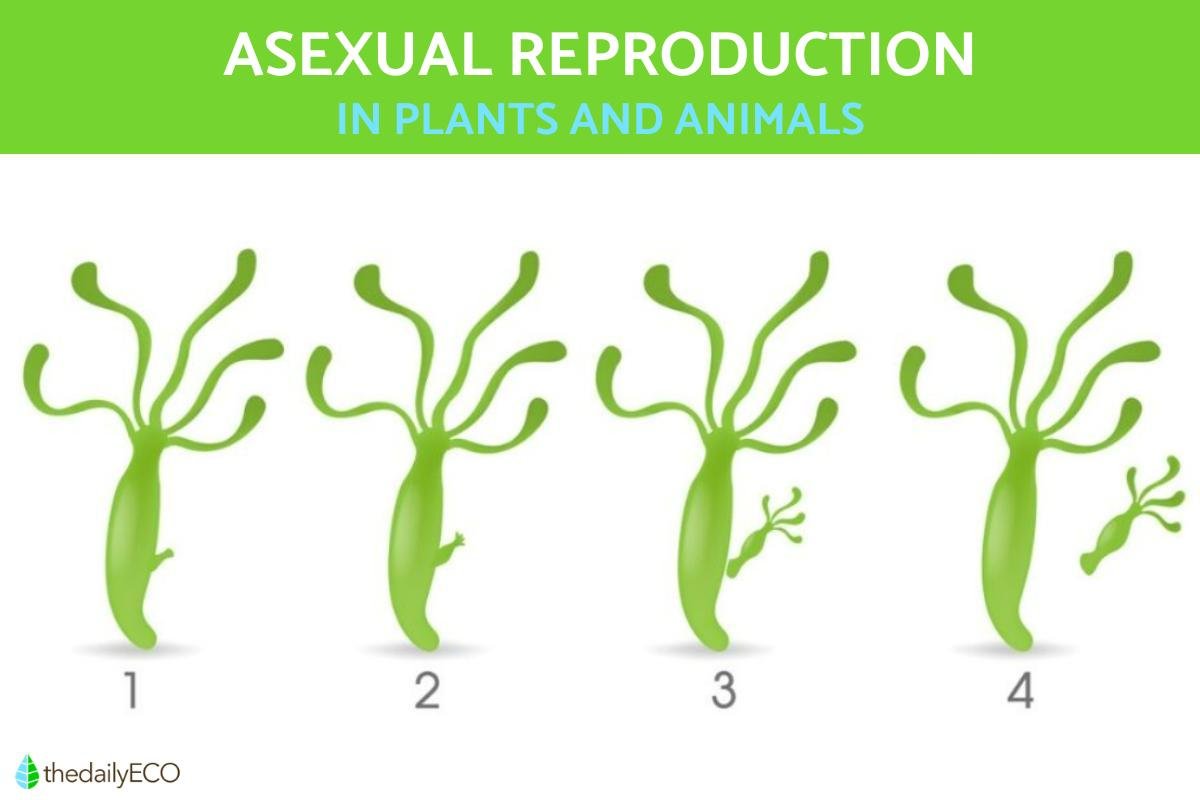

- Mode of Reproduction: Asexual reproduction (e.g., budding, binary fission) produces near-identical copies, while sexual reproduction generates diverse combinations.

- Mutation Rate: The frequency of errors during DNA replication introduces new variations into the gene pool.

- Number of Chromosomes and Extent of Crossing Over: A higher number of chromosomes and more frequent crossing over (the exchange of genetic material between homologous chromosomes during meiosis) both increase the potential for genetic recombination and variation.

- Individual Size (and related complexity/generation time): Larger, more complex organisms often have longer generation times, which can influence the rate at which new variations spread through a population.

- Population Size: Larger populations generally harbor more genetic diversity, making them more resilient to environmental changes. Smaller populations are more susceptible to genetic drift and inbreeding.

- Degree of Inbreeding versus Outbreeding: Inbreeding (mating between closely related individuals) reduces genetic diversity, while outbreeding (mating between unrelated individuals) increases it.

- Relative Amounts and Positioning of Haploidy and Diploidy: As seen in plants, the balance between haploid and diploid phases in a life cycle can influence how genetic information is expressed and passed on.

These factors are not isolated; they are deeply interconnected, with the chosen mode of reproduction influencing the variation present, and natural selection, in turn, constantly refining and modifying both the reproductive strategies and the mechanisms that control genetic diversity.

Our Own Story: The Human Life Cycle

The human life cycle is a quintessential example of sexual reproduction, a journey that begins with a singular, profound event: conception.

The Blueprint of Being: From Conception to Adulthood

At conception, the genetic material from two parents unites. Each parent contributes 23 chromosomes, resulting in a zygote with 23 pairs, or 46 chromosomes in total. This ensures a complete and genetically equal contribution from both mother and father, creating a unique individual unlike any other. This new genetic code then serves as the meticulous blueprint, directing every stage of development.

The Stages of Human Development

Our journey unfolds through clearly defined stages, each with its unique challenges and milestones:

- Prenatal Development: This nine-month period of gestation is a marvel of biological precision. The genetic code orchestrates an astonishing cascade of growth and differentiation, transforming a single cell into a complex organism with fully formed organs and limbs.

- Infancy and Toddlerhood: These are periods of extreme dependence, requiring extensive care, protection, and nourishment from caregivers. During this time, rapid physical and cognitive development occurs.

- Late Childhood and Adolescence: As individuals grow, they experience increasing independence, navigating social complexities, developing personal identities, and undergoing profound physical changes leading to sexual maturity.

- Adulthood: This stage marks the period where individuals typically reach full physical maturity and gain the capacity to procreate, thereby continuing the biological life cycle and ensuring the perpetuation of the species. It's the cycle's point of renewal, where the baton is passed.

An interesting aspect of human reproduction is how sex is determined: the father plays the decisive role. If the father contributes an X chromosome (like the mother always does), the resulting child will have an XX chromosomal pair, leading to a female. If the father contributes a Y chromosome, the child will have an XY pair, resulting in a male.

Offspring Care: Nurturing the Next Generation

The act of reproduction doesn't always end at birth or hatching. For many species, especially those that invest heavily in fewer offspring, offspring care becomes a critical extension of the reproductive strategy, directly impacting the survival and success of the next generation.

The Spectrum of Parental Investment

As briefly touched upon earlier, species have evolved diverse approaches to parental investment, typically falling along a spectrum:

- "Quantity Over Quality" (r-strategists): Many organisms, like certain fish, insects, or plants, produce an enormous number of offspring. The survival rate for any individual offspring is incredibly low, and parental care is often non-existent or minimal (e.g., simply laying eggs and leaving them). The sheer volume, however, ensures that at least a few will likely survive to adulthood.

- "Quality Over Quantity" (K-strategists): At the other end of the spectrum, species like mammals, birds, and many higher plants produce fewer offspring but invest heavily in their care. This can involve prolonged gestation, feeding, protection from predators, teaching essential survival skills, and even social learning. The goal here is to maximize the survival rate of each individual offspring.

Why Care Matters: Ensuring Success

Parental care, in its various forms, is a direct result of natural selection favoring behaviors that enhance the reproductive fitness of the parents. By increasing the chances that their offspring will survive to reproduce themselves, parents effectively pass on their own genes more successfully. This intensive investment is often linked to:

- Complexity of Development: Organisms with complex developmental pathways or long juvenile periods benefit greatly from sustained care.

- Vulnerability of Offspring: Young, small, or immobile offspring are often highly vulnerable to predation, disease, or environmental hazards, making parental protection crucial.

- Learning and Skill Acquisition: For species with complex behaviors or social structures, parents might actively teach their young essential skills, from hunting techniques to social norms, vital for adult survival.

The decision for a species to adopt one strategy over another—whether to flood the environment with countless tiny lives or painstakingly nurture a select few—is a profound evolutionary compromise, perfectly tuned to their specific ecological niche and environmental pressures.

The Continuous Thread: Life's Unfolding Tapestry

The journey through reproduction, life cycles, and offspring care reveals an astounding truth: life is an unbroken, self-perpetuating phenomenon. From the smallest bacterium splitting in two to the most complex human passing on a legacy, the fundamental drive remains the same—to create copies, to adapt, and to endure. Each species, whether it undergoes radical metamorphosis, alternates generations, or provides intensive parental care, has perfected its own intricate strategy for survival, ensuring that the grand tapestry of life continues to weave itself, thread by vibrant thread, into the future.

Understanding these cycles isn't just about cataloging biological facts; it's about appreciating the profound elegance and resilience of life itself, a constant process of renewal where every beginning is a continuation, and every end, a promise of new life.